Introduction

Brand remains one of the most influential yet least rigorously measured drivers of enterprise value. Its effects build over time, influencing demand, pricing power, and customer loyalty well beyond standard reporting cycles. By contrast, much of today’s measurement infrastructure, particularly Marketing Mix Modeling (MMM), has historically focused on short-term, in-period responses to media and promotional activity.

The consequence is a structural imbalance: organizations frequently measure incremental outcomes with precision but lack a disciplined framework for attributing long-term baseline shifts to the cumulative impact of brand-building investments. As emphasized in The Economic Value of Marketing, such omissions can lead to misallocation of resources, underinvestment in brand, and an incomplete understanding of marketing’s role in creating enterprise value, ultimately costing organizations millions in foregone revenue.

This white paper presents a technically grounded and empirically informed approach to overcoming that imbalance. It details how brand creates value economically, how it should be measured, how brand tracking must be structured to generate statistically valid time- series, and how brand metrics should be integrated into MMM using a structural long-term modeling architecture.

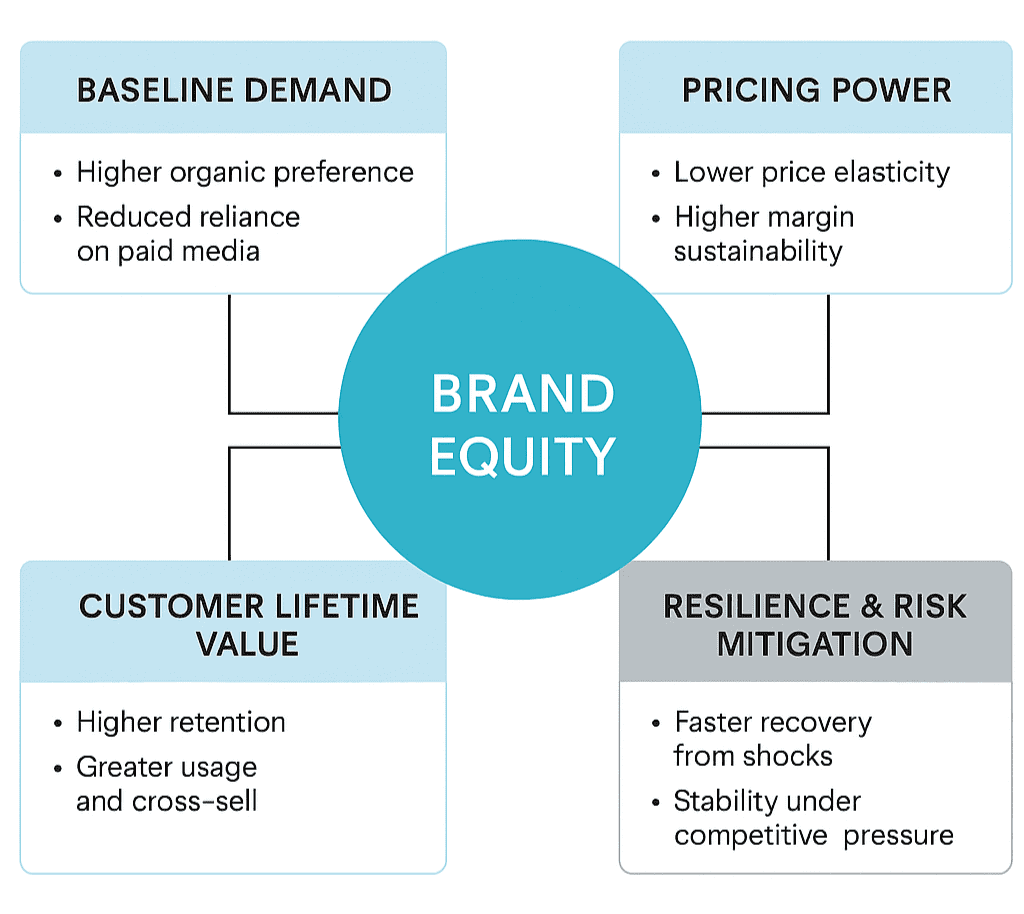

I. How Brand Creates Economic Value

Brand equity affects commercial performance through multiple interconnected mechanisms. These mechanisms operate structurally, not episodically, and their combined effects often exceed the immediate impact of paid communications.

The core economic channels through which brand creates value include:

Baseline Demand Growth

Strong brands command higher baseline demand because consumers perceive them as lower risk, more credible, or more relevant than alternatives. This structural preference reduces the marketing effort required to maintain share and stabilizes demand against competitive or macroeconomic shocks.

Pricing Power

Brands with strong equity face lower price elasticity, enabling firms to maintain or expand margins with minimal volume loss as customers are more likely to tolerate price increases without switching or reducing usage. This pricing advantage becomes especially valuable in categories where consumers perceive products as interchangeable, such as bottled water, household staples, basic financial products, or generic OTC medicines, because brand is often the primary source of differentiation.

Customer Lifetime Value Enhancement

The relationship between brand and customer lifetime value is particularly prominent in subscription, contractual, and high-frequency purchase categories. Examples include streaming services, mobile phone plans, insurance products, daily beverages, and personal care staples. In these categories, brand strength does not typically change behavior in dramatic ways; instead, it influences a series of small but economically meaningful outcomes: slightly higher retention, marginally greater usage, reduced churn, or a higher likelihood of adopting additional products. As discussed in The Economic Value of Marketing, these incremental behavioral shifts compound over time across customer cohorts, translating into materially higher lifetime value and long-term profitability, even when short-term sales effects appear modest.

Resilience and Downside Protection

Brand trust and familiarity help stabilize demand during PR crises, competitive disruptions, or regulatory changes by softening their impact on consumer behavior. Firms with strong brands typically experience smaller declines and faster recoveries.

These channels highlight a critical distinction: brand operates as a structural asset embedded in the firm’s economic environment. Its effects must therefore be measured and modeled on time horizons appropriate to such an asset, not on the short cycles used for incremental analysis.

II. Measuring Brand: Selecting Metrics That Predict Behavior

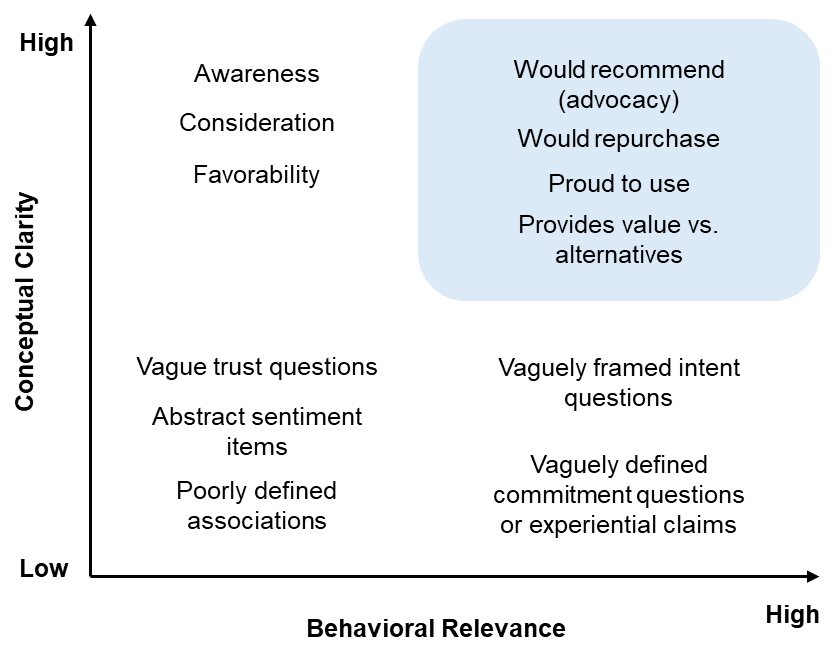

Although brand is structurally important, it is often measured through instruments that are neither behaviorally predictive nor statistically suited to econometric integration. Traditional tracking studies frequently rely on funnel metrics such as awareness, consideration, favorability, that describe sentiment but have limited power to predict actual economic behavior. These metrics tend to be highly correlated with one another yet weakly correlated with economic outcomes such as purchase incidence, retention, or price sensitivity. As a result, they offer little insight into the mechanisms through which brand equity translates into financial value.

This measurement gap carries real financial consequences. Organizations routinely invest hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars annually in brand tracking programs built around poorly specified metrics that lack predictive validity. When metrics fail to capture actual behavioral drivers, the resulting data, however precisely measured, guides decisions based on statistical noise rather than genuine consumer behavior.

Empirically stronger brand metrics tend to share two properties:

- They require evaluative judgment involving choice, trade-off or personal risk.

For a survey measure to be predictive of behavior, it must reflect how consumers actually think when making purchase decisions. This occurs in two ways:- First, the metric must involve some type of trade-off or choice, a judgment where one option is selected over alternatives, implicitly or explicitly. Questions like “Would you choose this brand over competitors at the same price?” put respondents in the same mindset they have when making real purchases.

- Second, the metric must put capital at risk, whether financial, social, or reputational. When consumers indicate they would recommend a brand to a friend or colleague, they're implicitly risking their own credibility and social standing. This personal stake makes the response far more predictive than abstract favorability ratings where nothing is at risk. Similarly, stating a willingness to pay a premium involves real financial trade-offs, not costless sentiment.

- They possess conceptual and linguistic clarity.

Consumers understand them intuitively, which reduces measurement noise and produces stable time-series behavior. For example, “Would you recommend this brand?” is far less ambiguous than abstract statements about whether a brand feels “modern” or “inspirational.”

In practice, the metrics that best meet these criteria are those that capture advocacy, repeat intent, and perceived relative value. Rather than reflecting momentary attitudes, these measures summarize the cumulative effect of prior experiences and capture consumers’ willingness to choose, stay with, or pay for the brand. As a result, they behave more like slow-moving indicators of underlying demand rather than like short-term sentiment scores. They also tend to exhibit greater stability over time, producing the kind of variance structure required for econometric modeling of long-term effects. Although many organizations accumulate lengthy lists of brand attributes, our evidence shows that a concise set of behavior-driven metrics provides a far more accurate read of brand strength and its relationship to long-run demand.

III. Best Practices in Brand Tracking for Econometric Use

Selecting the right brand metrics is a necessary starting point, but it is not sufficient on its own. Even behaviorally meaningful measures can fail to deliver insight if the tracking program lacks the statistical rigor required for time-series analysis. The effectiveness of brand measurement therefore depends not only on what is measured, but on how those measures are collected, maintained, and evaluated over time. MMM is particularly sensitive to noisy or low-frequency data, because brand effects unfold slowly and require sufficient temporal variation to be identified.

In this section, we outline the practical design principles required to ensure brand metrics form stable, interpretable time series suitable for econometric modeling.

Three principles govern the design of a tracking system suitable for MMM:

- Adequate Sample Density

Brand evolves slowly. For monthly or weekly data to be usable, the effective sample size per period must be large enough to minimize random variation introduced by the measurement process.

- Monthly tracking typically requires 300–500 completes per market

- Weekly tracking requires either significantly larger samples or rolling sampling

Although many tracking studies report large aggregate sample sizes, the effective sample available for each period, especially after segmenting by geography, user status, or demographic groups, may be insufficient. When sample sizes are too small, the resulting noise can appear as genuine shifts in brand metrics. These artificial fluctuations may correlate spuriously with sales or media inputs, contaminating long-term effect estimation.

- Consistency Over Time

Time-series modeling depends on comparable measurement across periods. Changes to fieldwork methods, question wording, sampling quotas, or weighting procedures create structural breaks that distort the series, impair comparability across periods, and can also be misinterpreted by the model as genuine changes in brand equity.

A robust tracking program should maintain:

- consistent questionnaire wording

- stable sample frames

- unbroken fieldwork cadences

- documented methodological changes

- Instrument Simplicity and Focus

Expansive attribute questionnaires increase respondent fatigue, reduce data quality, and raise costs without improving predictive power. From a modeling perspective, what matters is not the number of questions asked but the statistical quality of the resulting time series. A well-designed, streamlined tracking instrument, administered consistently over time produces cleaner, more stable data that can be interpreted reliably within an econometric framework.

Finally, practitioners should not hesitate to leverage modern sampling methods. Rolling sampling designs, AI-driven sample rebalancing, and synthetic augmentation can all improve statistical efficiency while maintaining cost discipline. In some cases, syndicated data (YouGov, Morning Consult, BERA, etc.) with continuous sampling frames may provide superior variance properties compared with bespoke tracking systems.

The objective is not to create a “perfect” brand tracker but a time series that captures genuine consumer shifts rather than artifacts of the measurement process.

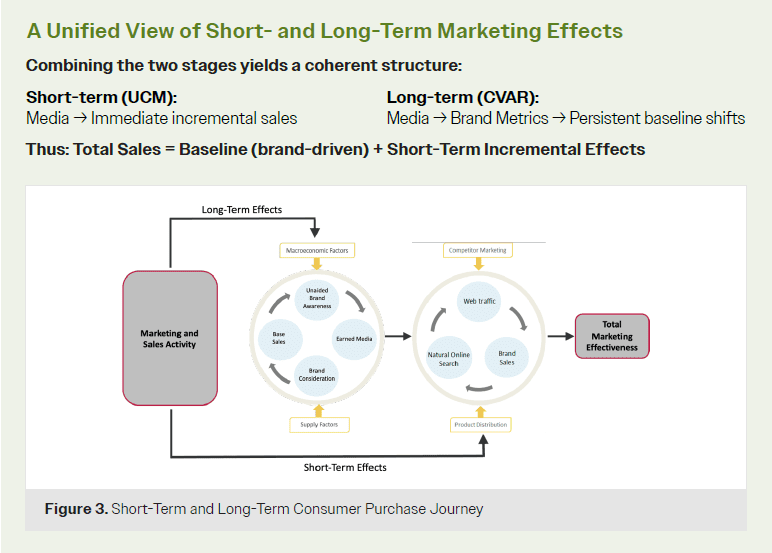

IV. Integrating Brand Metrics into MMM: A Structural Long-Term Approach

Integrating brand into MMM requires more than adding tracking data to a sales regression. Brand is slow-moving, cumulative, and deeply tied to consumer preference formation. To measure it correctly, MMM must separate short-term fluctuations from the long-term forces that determine baseline demand.

Integrating brand into MMM requires more than adding tracking data to a sales regression. Brand is slow-moving, cumulative, and deeply tied to consumer preference formation. To measure it correctly, MMM must separate short-term fluctuations from the long-term forces that determine baseline demand.

Marketscience’s methodology, detailed in our IJRM paper Modelling Short- and Long-Term Marketing Effects in the Consumer Purchase Journey, addresses this using a two-stage structural approach.

Stage One: Separating Short-Term Effects from the Baseline

The first stage uses an Unobserved Components Model (UCM) to decompose observed sales into:

- short-term incremental effects driven by media, promotions, and pricing

- seasonal and cyclical patterns

- a baseline trend capturing persistent consumer preference, competition, and macro conditions

This decomposition is essential. It isolates the slow-moving structural component of demand, which brand should influence, while preventing short-term noise from contaminating long-term estimates.

The extracted baseline becomes the brand-relevant part of the demand system.

Stage Two: Explaining Baseline Evolution Through Brand Metrics

The second stage models how the baseline evolves using a Cointegrated Vector Autoregression (CVAR). This structure tests whether brand metrics, earned media (e.g. social mentions), word-of-mouth, and baseline demand share a long-run equilibrium relationship.

This is the econometric definition of genuine brand-building: brand attitudes and long-term sales should move together over time.

When metrics cointegrate with the baseline:

- brand metrics become the mechanism through which marketing has persistent effects

- long-term effects must flow through brand, not directly from media to sales

- permanent shifts in baseline can be attributed to specific marketing actions

This corrects a long-standing issue in MMM, where long-term effects are often mis-specified using dual Adstock structures rather than proper time-series foundations.

This framework offers several advantages. It separates short-term efficiency from long-term effectiveness, ensuring that brand-building is measured in a manner consistent with the marketing science literature on persistence (see References). It prevents the common error of attributing short-term fluctuations to long-term effects (or vice versa) and allows analysts to quantify both the immediate incremental response to marketing and its slower, brand-driven impact on baseline demand. In doing so, it provides a statistically defensible way to connect marketing activity to persistent changes in consumer preference and, ultimately, to enterprise value.

Implications for Modeling Brand in MMM

This methodological framework implies several practical rules for integrating brand into Marketing Mix Models:

- Brand metrics should never be inserted directly into a sales equation as contemporaneous regressors.

If they move too quickly or inconsistently, this indicates measurement noise, and they will be rejected by the CVAR, not “forced” into a model. - Brand effectiveness is quantified through permanent changes in the baseline trend, not through short-term coefficients.

- All persistent effects must pass through the brand system.

A media channel has a long-term effect only if it produces a statistically significant and persistent shift in brand metrics that cointegrate with sales. - Not all brand metrics will cointegrate.

Those that fail to demonstrate a long-run equilibrium relationship with baseline demand should be excluded from long-term modeling. - The magnitude of long-term effects can be much larger than short-term effects, often exceeding them by a factor of 2–5 depending on category, consistent with empirical findings in the IJRM application.

Conclusion

Brand is a long-term, structural asset whose evolution and commercial impact must be measured with the same rigor typically applied to short-term marketing effects. Behaviorally anchored brand metrics, supported by statistically sound tracking and integrated into MMM through a coherent long-term modeling structure, allow organizations to quantify brand’s contribution to enterprise value with substantially greater accuracy.

When brand is modeled in this manner, MMM extends beyond attribution and becomes a strategic system for understanding how marketing creates value, both immediately and over time. This alignment enables marketers and finance leaders to collaborate on decisions grounded in a shared economic reality, improving investment allocation, long-term planning, and organizational growth.

References:

Bain & Company. (2012). Brand Strategy That Shifts Demand: Less Buzz, More Economics.

Binet, L. & Field, P. (2019). Media in Focus: Marketing effectiveness in the digital era. IPA.

Cain, P. M. (2022). Modelling Short and Long-Term Marketing Effects in the Consumer Purchase Journey. International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 39, No. 1, pp. 96–116).

Cain, P.M. (2025). Long-term advertising effects: The adstock illusion. Applied Marketing Analytics, Volume 11 / Number 1 / Summer 2025, pp. 23-42(20). Henry Stewart Publications.

Dekimpe, M., & Hanssens, D. (1995). The persistence of marketing effects on sales. Marketing Science, 14(1), 1–21.

Marketscience. (2024). Redefining Attribution In A Privacy-First World.

Marketscience. (2025). The Economic Value Of Marketing: A Financial Perspective.