For decades MMM has been seen as a way to identify the “50% of advertising spend that is wasted”. However, failure to acknowledge two fundamental issues will risk continued waste through misestimation of both Performance and Brand Marketing, resulting in suboptimal allocation of marketing investment and significantly reduced marketing effectiveness.

Modern Marketing Mix Models have focused on moving from a siloed view to measuring the cross channel and synergy effects that exist in today’s more complex path to purchase (Advertising Analytics 2.0, Harvard Business Review, 2013). Such approaches claim to provide a more realistic estimate of Return on Marketing Investment, directly addressing the oft-quoted remark from a Fortune 200 CFO: “When I add up the ROIs presented to me from each of our silos, the company appears twice as big as it actually is.”

However, as outlined in the latest Marketscience peer-reviewed IJRM publication “Modelling short and long-term marketing effects in the consumer purchase journey”, today’s conventional MMM still fails to address two fundamental problems, leading to continued misestimation of marketing effectiveness and a lack of credibility with Finance departments.

1. Selection bias of last touch acquisition marketing channels

With the advent of digital media, the marketing response model has evolved to capture a modern paid, owned, earned media structure. This typically takes the form of a nested sequence of regression equations, where paid marketing works through intermediate own and earned media touchpoints to drive sales/business outcomes. Such a ‘consumer-journey’ approach is designed primarily to deal with last-touch attribution problems, helping to reattribute a part of a last-touch medium such as paid search back to sources earlier in the chain such as TV advertising.

With the advent of digital media, the marketing response model has evolved to capture a modern paid, owned, earned media structure. This typically takes the form of a nested sequence of regression equations, where paid marketing works through intermediate own and earned media touchpoints to drive sales/business outcomes. Such a ‘consumer-journey’ approach is designed primarily to deal with last-touch attribution problems, helping to reattribute a part of a last-touch medium such as paid search back to sources earlier in the chain such as TV advertising.

However, this ignores the inherent selection bias of online media such as paid search. Selection bias occurs when a (part of) the impact of a ‘treatment’ on an outcome variable is caused by a factor that predicts the likelihood of selection into treatment rather than due to the treatment itself. For example, regression models measuring the impact of years of education (the treatment) on earnings potential (the outcome) are inherently biased since those with higher ability are more likely to opt into more years of education and would have earned more anyway. Without controlling for latent ability, the regression parameter is subject to (positive) endogeneity bias - a problem that has received much attention in the economics literature.

So it is with paid search and other 'last touch' media. Simple regressions of sales on search clicks – a component of site visits – are biased since those consumers with the highest propensity to buy are more likely to take part in the paid search ‘treatment’. Such latent purchase predisposition implies that a large part of paid search is simply an artefact of the sales process and we are essentially regressing a part of sales on itself. As such, sales and search could equally well be reversed in the chain, leading to a simultaneity or endogeneity problem.

Without accounting for the likelihood of this type of chain-reversal, the sales impact of paid search predominantly captures simple correlations rather than meaningful causal effects. This leads to biased estimates of the search-sales impact and all marketing effects that work through it. Consequently, even if offline TV advertising does lead to more branded search activity, it does not necessarily mean it drives incremental sales in this way.

2. Credible representation of long-term brand-building

Conventional mix models focus on short-term ‘transitory’ lifts in sales and how marketing programs drive consumers through the path to purchase. However, marketing can also create brand-building effects through emotional brand associations and customer experiences that improve perceptions and drive long-term base sales. Long-term effects, therefore, are not simply an extension of short-term effects but derive from a fundamentally different type of consumer behavior.

A common approach to incorporating brand-building effects augments the mix model with survey-based ‘mindset’ metrics such as unaided brand awareness or brand consideration, together with sub-models for the chosen metric in terms of advertising variables. The indirect effects of advertising on sales are then interpreted as long-term effects. However, this is inherently flawed for three reasons:

- Firstly, if mindset metrics are to form the basis of a plausible theory of brand-building, they should be linked directly to base sales. This is simply because base sales and mindset metrics are alternative measures of underlying brand health: the former through long-term revealed purchase behavior, the latter through stated consumer attitudes. As such, they are two sides of the same coin. Observed sales obscure long-term movements, risking contamination with short-term effects.

- Secondly, if mindset metrics are to provide a credible statistical foundation they need to explain the base sales evolution inherent in genuine brand-building: that is, share a common trend with sales and cointegrate to form equilibrium relationships. However, sales evolution is ignored and the impact of advertising on mindset metrics is deemed to reflect brand-building behavior per se.

- Finally, simply adding brand perception metrics as regressors tells us nothing about the mechanics of brand-building. Namely, how base sales, brand metrics and earned media interact and drive each other to explain how persistent brand loyalty is created and how brand-effects wear in/accrue over time.

A more appropriate model

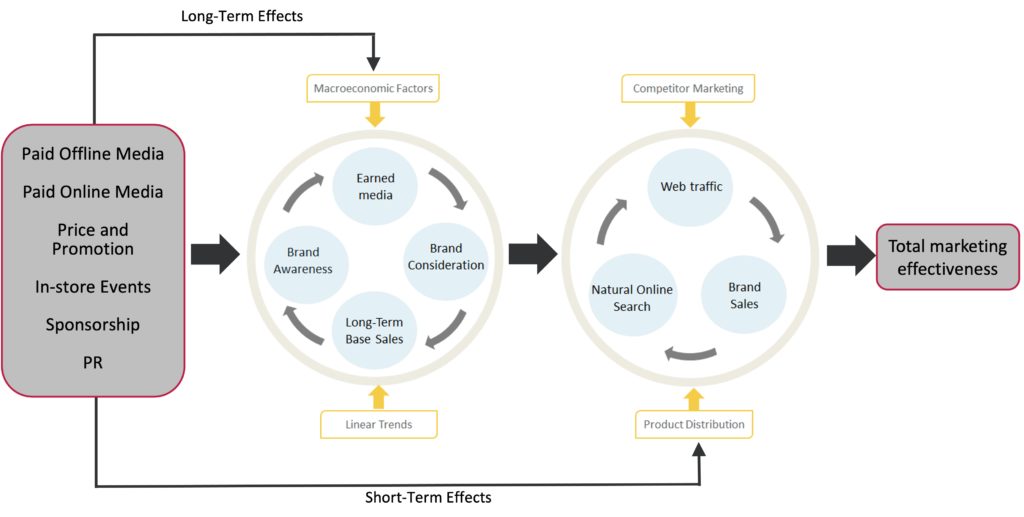

A truly holistic view of both the short and long-term role of media requires an alternative approach to the mix model: one combining flexible short-term estimation with an explicit model for brand-building, where the long-term preferences embodied in attitudinal data are causally linked to long-term preferences reflected in base sales. Only then can mindset metrics provide a credible structural foundation for the brand-building effects of advertising. This idea is illustrated in Figure 1, depicting a network view of short-term sales and long-term brand-building.

Figure 1: Short-term sales and long-term brand-building networks

This structure creates richer and more credible mix models, informing a much wider set of decisions faced by Marketers today, including the long-term impact of many other operational programs such as customer experience, product development, distribution and pricing.

We will be sharing more on the details of this approach in a series of blogs. Meanwhile, to learn more about the technical aspects and the underpinnings of BaseDynamics, our proprietary approach to MMM, click here. To read the paper abstract click here.